Traveling Exhibits

An Illuminating History

Traveling exhibit from the University of Paris Rare Books Collection

Loyset Liédet and Pol Fruit (Flemish)

Written 1463-1465, Illuminated 1467-1472

Tempera colors, gold leaf, and gold paint on parchment

In the early Middle Ages, manuscripts were largely produced by monks in monasteries for the use of the Catholic Church. During the Gothic era, however, cities teemed with students, tradesmen, aristocrats, and churchmen, who all clamored for illuminated manuscripts.

The art of manuscript illumination became the province of professional artists living in rapidly expanding urban centers. Manuscripts designed to inspire devotion as well as to instruct and entertain were commissioned by a wide variety of individuals.

Scenes reflecting aspects of daily life and society in the Middle Ages began to appear on the pages of a growing assortment of illuminated books— devotional works, law texts, scholarly literature, and romances—that might be written in either Latin or, for the first time, a local European language.

This exhibition showcases a range of books, from lavish prayer volumes and Bibles, to illustrated scientific texts and romances produced in various parts of Europe between 800 and 1500 A.D.

The increase of trade and growth of cities throughout Europe during the Gothic period meant that patrons and artists traveled more frequently, bringing with them artwork and styles that encouraged artistic discourse across regions.

In the north, the style of manuscript illumination that emerged around 1200 was distinguished by naturalism tempered with courtly refinement. The art of ancient Greece and Rome as well as that of the Byzantine Empire influenced developments in southern Europe.

Other art forms also influenced the painted page, such as stained glass, with its emphasis on geometric shapes and the predominant use of red and blue.

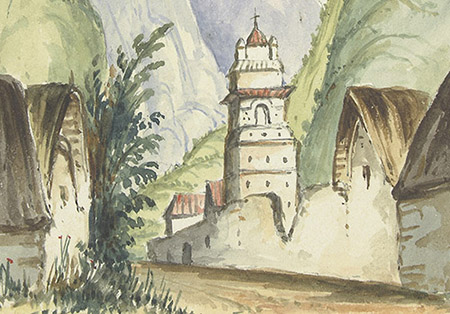

Four Centuries of Watercolors

Traveling exhibit from the Museo di Palazzo Reale/Genova

Pancho Fierro, 1803-1879

Watercolor on paper (ca. 1853)

This exhibition traces the development of watercolor as an artistic medium and documents the inventive techniques of several great watercolorists.

The ingredients of watercolor are simple: cakes or tubes of paints, brushes, water, and paper. Enormous skill, however, is required to master the medium. The greatest watercolor artists developed unique and inventive ways of manipulating pigment, water, and the paper underneath.

Flemish artist Anthony van Dyck pioneered the use of translucent watercolor washes. The artist allowed the blank paper to shine through the pigment, playing as important a role as the watercolor itself. From van Dyck’s time on, watercolorists viewed their medium as an interaction between color and paper rather than simply laying down pigment.

The paint we call watercolor had its beginnings in the late 1400s. Well suited to field studies because of its portability, watercolor quickly became popular for landscapes and natural history studies.

Watercolor gained in popularity and prestige starting around 1780. Landscape artists in Britain led the way, using watercolor to record nature. With the founding of the Society of Painters in Watercolours in London in 1804, watercolorists were gaining acceptance as serious artists.

Watercolor reached new artistic heights in the late 19th century. Works in watercolor from this time are characterized by brilliant color and bold brushstrokes also occurring in oil painting. The late 19th century saw the growing prestige of watercolor as an artistic medium, which freed artists from having to compete with oil painting.

Images in Light: Stained Glass

Traveling exhibit from the British Museum, Opening October 30

Unknown maker, Swiss; Circa 1490

Pot-metal, flashed, and colorless glass, vitreous paint, and silver stain; lead came added

One of the most widespread forms of painting, stained glass inspired the the faithful through religious narratives in churches, celebrated family and political ties in city halls, and even decorated the windows of private houses.

Some of the most powerful art produced in the High Middle Ages were stained-glass cycles, or visual stories, in French cathedrals. (Among the most famous of these is in Reims Cathedral.)

By the late 1400s glass became more affordable; houses were increasingly fitted with clear glass windows, sometimes inset with small stained-glass panels.

The production of large-scale stained-glass windows for churches flourished in Europe during the Renaissance.

During the late 1400s glass windows in domestic interiors became ubiquitous, and small painted roundels became so popular that their production reached nearly industrial proportions by the 1520s. Purchased in large cycles or as single images, they were intended to amuse and instruct, with subjects like zodiac signs, portraits, and heraldry.

In the playful stained-glass window shown below, a red boar on a family’s coat of arms comes to life. The beast appears sly, even a bit threatening, as he stalks an innocent looking maiden strolling under an archway. The woman coyly pretends not to notice him while hiding a dagger in the folds of her dress.

The richness of this window’s design reflects the joyful spirit of the Renaissance. By then, the dark look of stained-glass windows had given way to a more colorful, light-filled aesthetic. As stained-glass windows became more affordable, people installed them in their homes. Subject matter changed, more often commemorating family and daily life.